Introduction

Given the significant decline in the Japanese Nikkei index, the largest since 1987, and the Bank of Japan’s current economic challenges, it is timely to explore one of the most widely used leveraged trades: the Japanese Yen Carry Trade.

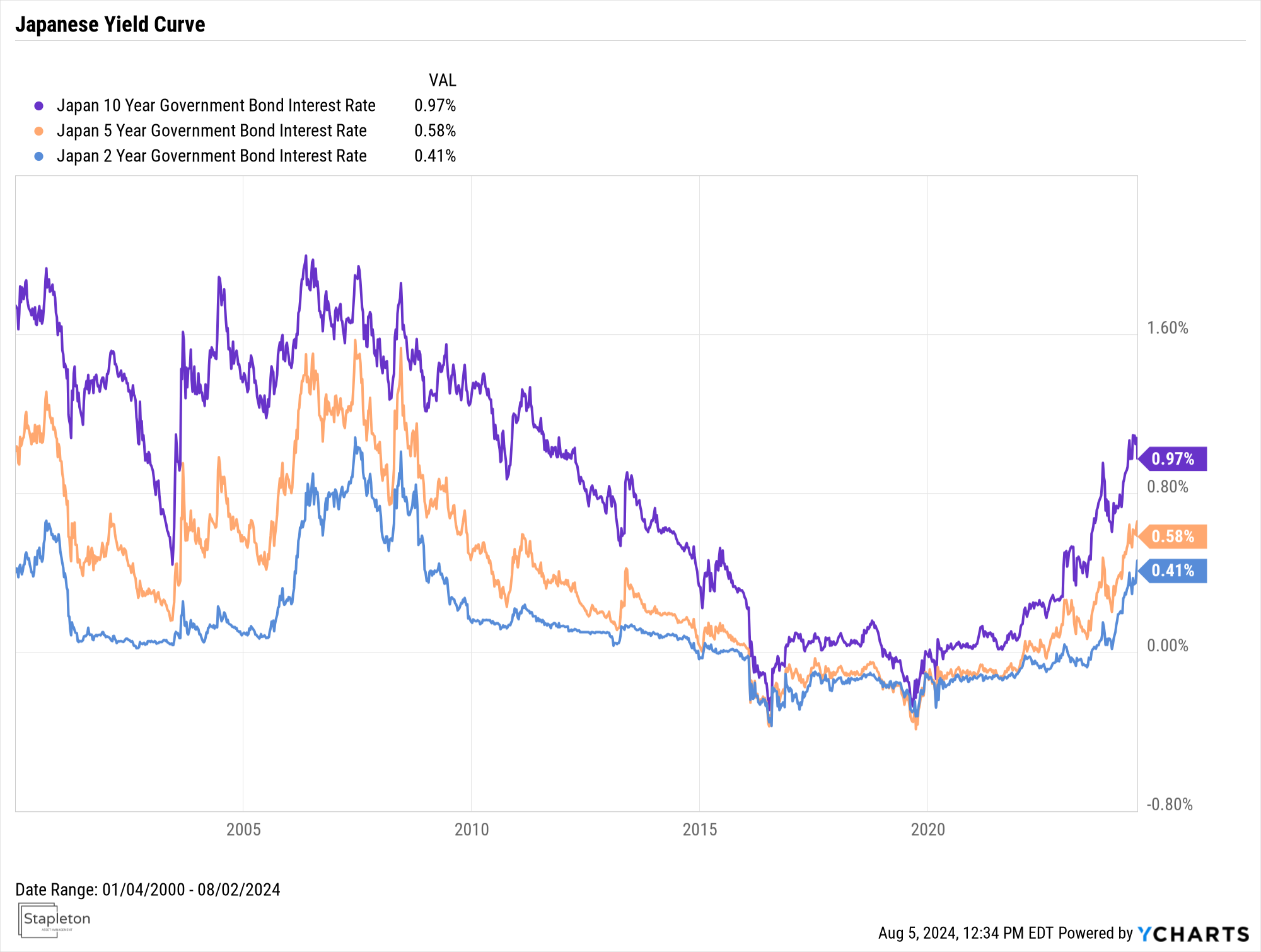

The Japanese Yen Carry trade has been prolific at investment managers around the world for the last 25 years since the Bank of Japan has been fighting deflation with very low interest rates:

As you can see above, interest rates between 2 and 10 years have mostly been below 1% which has made it extremely cheap to borrow money in Japan. Between 2016 and 2020, Japan experienced a period where interest rates were negative and you would be paid to borrow money in Yen.

Mechanics of the Carry Trade

After borrowing Yen at low rates, investors typically convert it into a higher-yielding currency rather than investing in Japanese assets, businesses, or real estate. They then invest in bonds or other assets in the higher-yielding currency, aiming to profit from the interest rate or return differential. That is the yen carry trade.

Now that the Yen has been borrowed at a cheap rate, what do you do with the funds? The cleanest and safest investment is to convert to a currency that has higher yielding government bonds and a strong currency. An example would be to borrow in Yen and invest in Australian government bonds with the Australian dollar. As long as the Japanese Yen remains where it is and the yields remain where they are, you can earn the spread between the interest rate paid on the borrowed Yen versus the interest rate earned on the Aussie government bond.

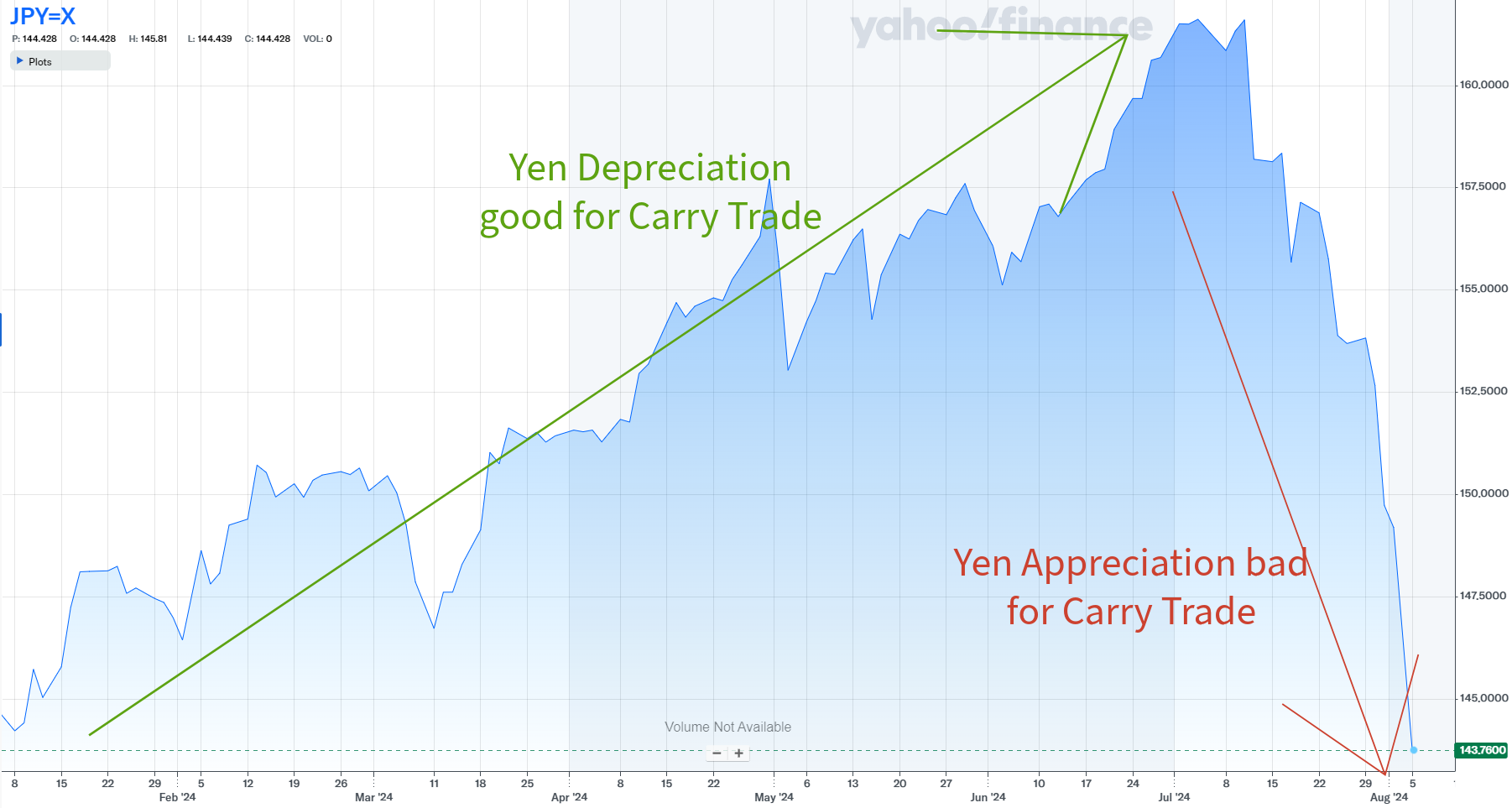

Nothing is risk free. Borrowing in Japanese Yen exposes investors to currency risk, as they are effectively shorting the Yen. If the Yen appreciates versus the currency that you converted to, then it is more expensive to pay back the loan. If the Yen depreciates versus the currency that you converted to, then it is cheaper to pay back the loan. The risk is also related to the term at which you borrowed money and the interest rate that is embedded in the loan. If you borrowed at a floating 1-month Japanese rate, the interest that you pay back increases as the 1-month Japanese rate increases. Both of these market movements can make the carry trade a pain trade which can result in significant financial losses.

Earlier this year, the Yen weakened significantly, declining approximately 40% against the US dollar. On July 10, the Bank of Japan announced the end of its negative interest rate policy, raising the short-term rate from -0.1% to a range of 0-0.1%. That marked the end of an eight-year period of negative interest rates. This decision was influenced by strong wage growth and a healthy economy. The outcome was a tremendous rally in the Yen versus the dollar which basically erased the depreciation YTD:

When the borrowed currency (Yen) appreciates beyond the loan initiation level, investors are incentivized to repay the loan quickly to avoid future losses due to further appreciation. That means that the participant in the carry trade must liquidate the assets that he/she purchased, convert the currency back to Yen, and then pay off the outstanding loan balance.

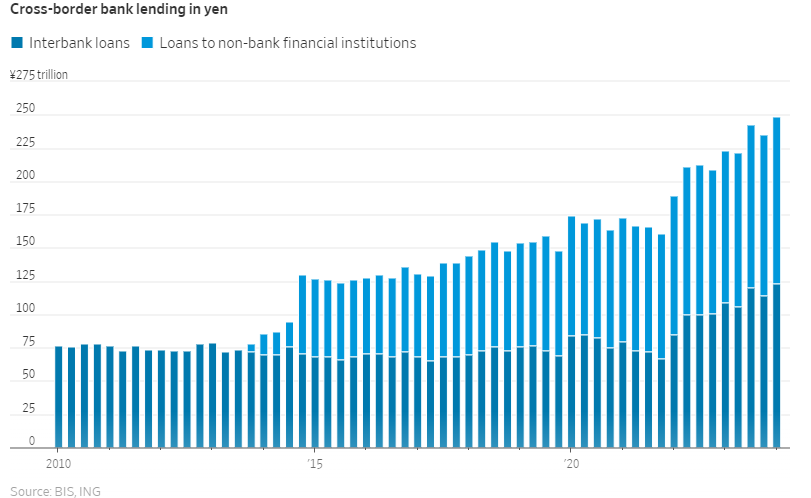

So where does that leave us? With the question of how big the Yen Carry Trade is as well as where it has been invested. The size is well over 1 Trillion $:

Implications for Investors

The Magnificent 7 Stocks in the United States are down over $3 Trillion from their highs and you can rightfully assume that some of that was liquidated to pay back loans dominated in Yen. It remains to be seen if this will contribute to a potential correction in the valuation bubble of Artificial Intelligence (AI) stocks. Finally, we must consider whether weaker economic indicators and a retreat in the ‘Magnificent 7’ stocks will trigger a broad repricing of all risky assets.

Comments are closed